Submitted by J. Grosse on Thu, 17/04/2025 - 09:51

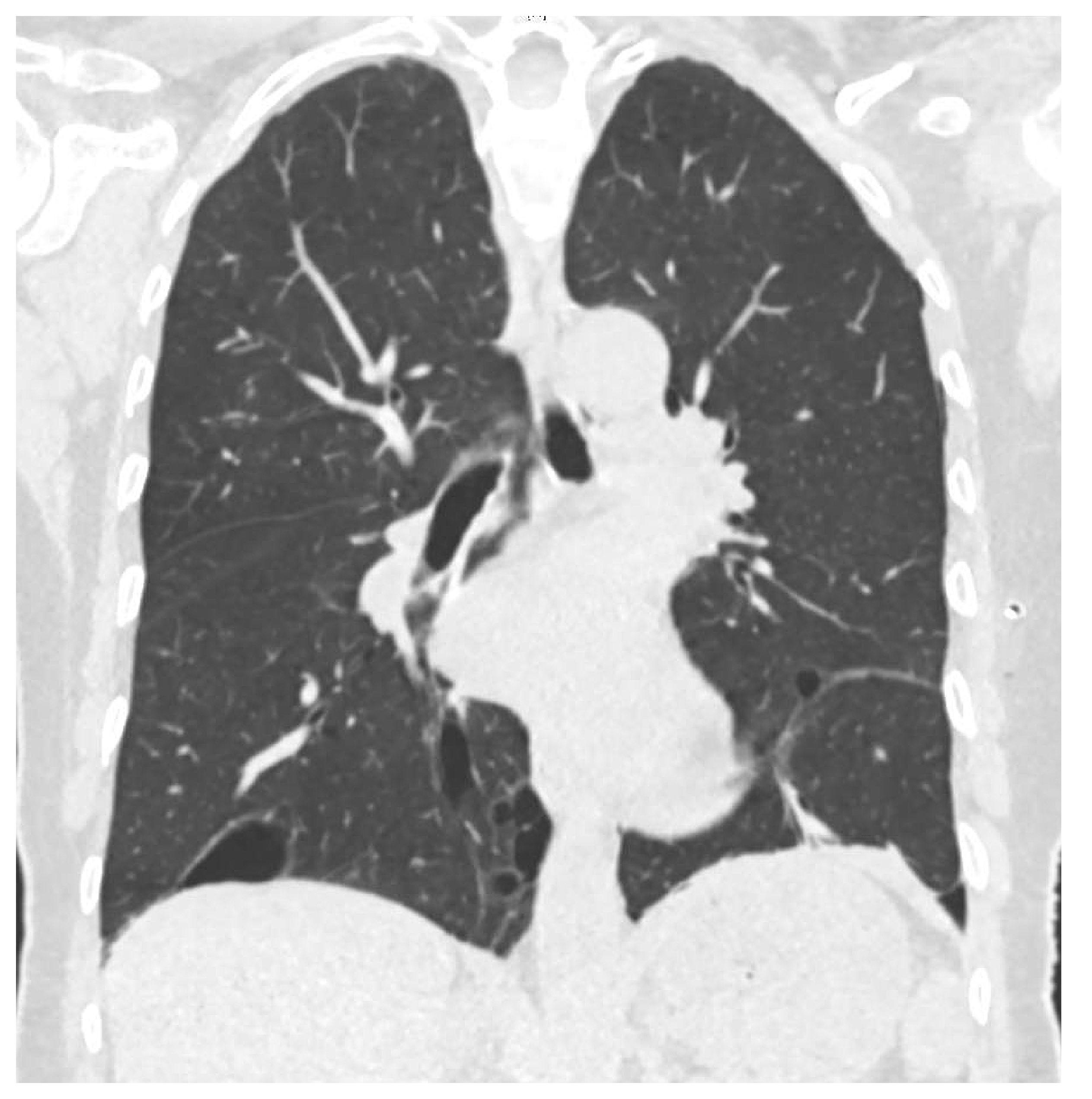

New research from Prof Stefan Marciniak and colleagues has shown that as many as one in 3,000 people could be carrying a faulty gene which significantly increases their risk of suffering a punctured lung. The gene, FLCN, is linked to Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (BHDS), symptoms of which include benign skin tumours, lung cysts, and an increased risk of kidney cancer.

As well as being a CIMR principal investigator, Prof Marciniak is an honorary consultant at Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Royal Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. He co-leads the UK’s first Familial Pneumothorax Rare Disease Collaborative Network together with Prof Kevin Blyth at Queen Elizabeth University Hospital and University of Glasgow.

In this study published Thorax, data from three large genomic databanks was examined. It was discovered that between one in 2710 and one in 4190 individuals carry the variant of FCLN implicated in BHDS, while the frequency of the disease itself is much lower, affecting only around 1 in 200,000 people. For those with a diagnosis, there is a lifetime risk of 37% of developing a punctured lung; however, curiously among all carriers of the faulty gene this risk was lower at 28%. Furthermore, patients with BHDS have a 32% chance of developing kidney cancer, but the wider community of carriers of faulty FLCN have a significantly lower risk of just 1%.

The finding that FLCN mutation carriers are much more common than previously supposed should encourage the application of genetic testing for BHDS in individuals with familial or recurrent pneumothorax or familial or multiple renal carcinoma, even if a family history or other features of BHDS are absent.

Professor Marciniak says he was surprised to discover that the risk of kidney cancer was so much lower in carriers of the faulty FLCN gene who have not been diagnosed with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome.

“Even though we’ve always thought of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome as being caused by a single faulty gene, there’s clearly something else going on,” Professor Marciniak said. “The Birt-Hogg-Dubé patients that we've been caring for and studying for the past couple of decades are not representative of when this gene is broken in the wider population. There must be something else about their genetic background that’s interacting with the gene to cause the additional symptoms.” He does not believe that it would be necessary to screen all carriers for kidney cancer however: “With increasing use of genetic testing, we will undoubtedly find more people with these mutations,” he said, “but unless we see the other tell-tale signs of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, our study shows there's no reason to believe they’ll have the same elevated cancer risk.”